Violence in the Stacks

News From the Stacks: Blog Blurb no. 4

Blurber: Lou Ryan

Violence in the Stacks

Late at night after everybody has gone to bed and only the cats and I are left awake, albeit in a semi-stupor (both the cats and I), we manage to catch sight of and latch on to new movies and series, all of which, it eventually turns out, come from books. Sometimes the excitement of the video version of the printed story is enough to get me primed for rummaging through the stacks in order to find the original texts. Such was the case for the John Carter tales, created by Edgar Rice Burroughs starting in 1912, which contain enough resource material for several big-screen pics, I’m sure, and which I found sufficiently literary, and poetic, to justify reading them. I do not hang my head in shame in front of my literary colleagues for having read visionary authors like Burroughs or Verne or Nicolas Camille Flammarion. This was Science Fiction in its infancy, when it was stretching its legs for a three-century run—or more!—and imagination was rampant with glorious epic amalgamations of the Song of Roland, of science and its weird discoveries of incredible new life forms on earth, of astronomical perspectives that resulted in unfamiliar territories with deviating gravitational pulls, and these magnificent authors wove their magic by intertwining the warp of history with the woof of futuristic interpolations, and the result was magic. Fantasty did this as well, for the Druids left their indelible mark on Tolkien’s hobbit tales, as did the Vikings, with a bit of lagomorph natural history thrown in, for the furry parts and the round warren abodes; and the poisonous contamination of the Industrial Revolution combined with the devastation of World War gave form and incorporeal substance to the menace of evil.

I haven’t been able to find the source material for the series Vikings, although it “reads” literary, but Game of Thrones certainly comes from books, although in this case I have not run out to get them, same as Cloud Atlas, for these tomes compete with the intricacy and breadth and depth of the Tolkien and Burroughs sagas, and, uh… well, just how many of these universes can I stuff into my mind? I’m no longer a spring chicken, I’m more like an autumn rooster, a bit bedraggled and crowing just a little, not quite ready for the coq-au-vin pot, and there are so many other books I need, and want, to read, that these painstakingly elaborate, monolithic, multi-tomed chronicles make Honoré d’Urfé’s L’Astrée look like a Maupassant hors-d’œuvre. You don’t bite into Cloud Atlas; it consumes you, taking you in and thrashing you to within an inch of your life. What is spit out, well, I wouldn’t consider it human. I confess that I’ve never read through to the end of Proust’s megagiga À la recherche du temps perdu, begun in 1913, (I forget what the latest official translation of the novel is in English, so here’s mine: On the lookout for lost time); but one courageous day, when I have ninety such courageous days lined up like a row of ducks, I’ll plunge myself in it, as a reward for good behavior. I’m surrounded by friends who, on a regular basis, disappear from view while Proust zaps them into another time and dimension, coming out sporadically to care for their physical needs before submerging anew to revel in the Proustian universe. I envy them that pleasure.

For now, however, getting back to these late-night viewings, I’ve noticed the elevated amount of violence in these shows. Oh, conflict gives rise to violence, I know, and Tristan must fight dragons and monsters before he can deserve the love of Isolde, but this latest batch of shows have killing sprees to make you gasp in awe, tidal waves of sword-clanking, helmet-crushing soldiers locked in bellicose embrace, and a plethora of super-gratuitous individual episodes that remain indelible in your memory for their ghastliness, like the grisly look of surprise on a victim’s face when he sees the tip of a blade slide out of his mouth: when the camera pans out we see the rest of the sword imbedded into the back of his skull. Oh, and when King Joffrey gets his send-off into the next world, by being poisoned during his marriage feast: what subtle writhing, what artful gasping, what picturesque bloodletting, copious out of mouth and nose, do we witness as he mutely beseeches his mama, and as he points a sinister finger at his uncle, the dwarf Tyrion Lannister. Boy, we almost know that Tyrion is not the culprit, but we do know positively that the sympathetic (and book-learnèd!) uncle has more to suffer under the posthumous influence of the nefarious nephew in order for the sordid tale to go on. I can barely manage to hang on.

I am not here to raise my accusing finger at art, nor call it the culprit for all that ails our society: kids see movie, movie shows mayhem and savagery, kids try it out for kicks. From reel to real (this metaphor worked better when movies were on reels); alright, from digital to physical, violence is transferred, via mental cases who conflate fiction with the real world, who confuse fantasy with actuality, who no more can separate dream from reality than voices in their head from the voices of people who physcially surround them. Art is not responsible for this; it’s the social net that is at fault, for it doesn’t capture these loose-minded people before they commit their atrocities. You’d think family members would have a clue that one of their own was building bombs in the basement.

The mother: “Honey, what’s that smell coming from the basement?”

The father: “Well, I don’t know, hon, let me take a whiff. Why, that’s nitric acid from drain cleaner, sulphuric acid from rust remover, with a soupçon of acetone from nail polish remover. We’ll just close the door so the smell of your chocolate banana bread isn’t ruined.”

The mother: “Oh, sweetie, that’s not chocolate banana. That’s trinitrotoluene that I’m mixing with ammonium nitrate. I love the smell of ammonal in the morning!”

The reason why I’m mentioning all of this is because, because, oh, boy, I’m going to get into trouble over this. It’s a good thing my byline is but an anagram of my real name. Every once in a while, since I’m a writer—you realize that all of this is for the sake of my writing, don’t you?—very seldom, you know, I get to fantasize, while I’m running through the paces of real life, and let me tell you now, I’ve never confused real life with the interior life that my imagination sometimes takes. Not very often, while I’m working at the bookshop, I get critical of certain customers who do certain things that really get on my uncertain nerves. These tend to be repeat customers, and they tend to be what I call monolunatics: they’re crazy about one thing, only one thing, and that’s all they ever look for. Like this older “gentleman” (and I’m using this socially neuter word as a homonym of the phrase I’d prefer to be using, this god-damned fucking older son of a bitch bastard moron, José Guerra—his real name, which I keep for the reverse irony, but which he’ll never find in this blog because he’s as ignorant as dirt—comes in, at least once a week, looking for books on war (guerra, in Spanish). He’s lived in the United States for half his long, wretched life, a life of exile, which I’m sure is difficult and painful and a life he never wanted, and that is the reason behind the fact that he never learned English, because he never wanted to be here in the first place. Thus, whenever he comes in, he looks only for war books written in Spanish, or translated into Spanish. I used to help him a lot, using either my Apple laptop, or my iPad, or my iPhone, whatever I had brought into the shop that day, trying to find out if our English titles on war had translations into Spanish. Most of the titles had not been translated into Spanish, and one day, out of frustration at not being able to purchase them in his language, he blurted out to me, “Well, if you use these old apparatuses (aparatos, in Spanish), no wonder you can’t find anything!” I looked at him in wonder, for I sincerely thought I was doing him a favor, for the twentieth time. But certainly for the last time. I abruptly closed my old apparatus, my antiquated iPad, gave him my back, and proceeded to work on the task which he had interrupted. From that day on, I never said hello, never looked into his piggy eyes, nor did I ever make the mistake of pretending that he existed.

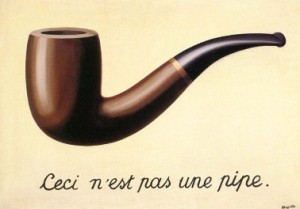

However, I never forgave myself for my lack of courage. I should have, in silence, pulled the nearest bookcase on top of him and crushed him, like the narrator in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart crushes his victim beneath the bed. I should have brought down the yardstick hard on his head, like Dostoievsky’s Raskolnikov brings down the axe on the pawnbroker bitch and splits her skull, in Crime and Punishment. I should have plunged the pair of scissors into his chest like the Professor in Ionesco’s The Lesson, who stabs and stabs his student for her smart-alecky responses. I should have thrown him into the back room and sealed it, like in Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado. I should have poisoned him the way Flaubert’s Madame Bovary poisons herself. I should have defenestrated him from an upper floor, the way Quasimodo flings down the wicked Frollo in Victor Hugo’s Notre Dame de Paris. I should have thrown him under a train, or at least under a bus, following the way Anna Karenina does away with herself in Tolstoy’s novel of the same name. I should have tortured him, hanged him, then burned him, like the Portuguese do to their victims, Candide and Pangloss, in a big auto-da-fé, in Voltaire’s Candide. I should have drowned him like Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, had him guillotined like Julien Sorel, in Stendhal’s The Red and the Black, or had him tied to a pit under a razor-sharp blade swinging on a pendulum to cut him in half (Poe, once again, in his Pit and the Pendulum; Poe is very good for this!). So, you see, other author’s imaginations rush to the memory to help out in times of frustration. That these actions are violent is well-known, for many of these stories have been around for a long time. That these actions lead to copy-cat killings is an entirely different scenario: I for one am appeased by my flagrant fantisizing, which remains within the confines of my skull. The act of thought does not lead to the doing of the act. Just like in René Magritte’s magisterial painting, The Treachery of Images, what you see is not a pipe.

What is it that you see, then, if this is not a pipe? You silly! This is an image of a pipe, not the pipe itself! So, if you could look inside my brain and visualize the images that are produced in that secret, private place, you would be apt to see murder and mayhem, violence and treachery. Mais non, ceci n’est pas une pipe. Ceci est l’image d’une pipe. Boy, you’re reading French! And understanding it, too!

The arsenal that we writers, and I must say, that the poets, especially, with their sacred role of furore poeticus that makes them the seers of society, the arsenal, I repeat, that we must in our brains keep and cultivate and indulge, like a greenhouse of living images and snippets and episodic mementos, is huge, and sometimes overwhelming. I, for one, am not a good conversationalist, in the physical world, for when anyone says anything, my mind parses it and sends the syntactic components through the sieve of my mind, twisting it this way, then that way, shaking it for its constituent meanings, comparing it to the bank of rhetorical devices that always live in my head, and by the time I come out with my retort, my interlocutor has had another cup of tea, looked at the sky to check for bad weather, looked at her watch, then gone off to catch the other guys for lunch. In my mind, however, in my mind where words are not spoken, where rhetorical meanings are zapped telepathically in transcendental immediacy, the images, the metaphors, the connotations, the sense of things is swift. But to say what I mean, that becomes agonizingly slow, with each word being chosen assiduously, each word precipitating out of the forest of trees that grow in my head.

Ah, I can hear it now! “He can’t see the forest for the trees.” Well, everybody gets lost in the details, sometimes. Flaubert flailed over the choice of certain words, but, in the end, he kept his images true and strong. Call me a dreamer, to compare myself to Flaubert, but if I use him as a model, it can only be beneficial to me. I suppose I am a dreamer, but it’s these dreams, these thoughts that I cultivate, these products of nerves, synapse and electricity that I encourage, that I husband greedily, that I squirrel away in my inner arboretum. And, yes, it’s all in my head.