LEARNING BY HAND: HELEN AT THE FAIR

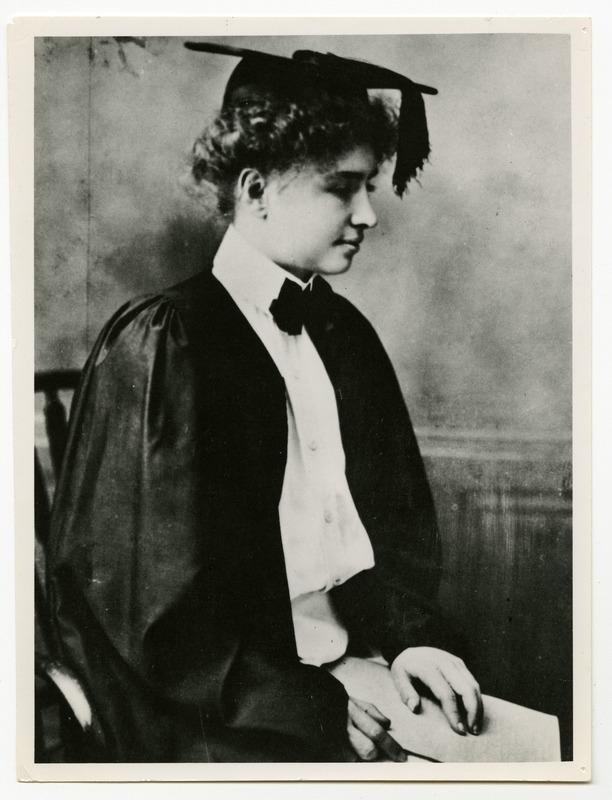

Hellen Keller, graduate of Radcliffe College

Helen Keller could draw a crowd. A public figure from an early age, constantly watched and petted, her unusual condition provoked a spectrum of reactions from pity and adoration to morbid curiosity and dread. What was the attraction? How did she elicit sentimentality while at the same time stirring up primal fears? A single day provides a window through which to see not only Helen, but the idea of Helen, a screen upon which the nation could project its dreams as well as its nightmares.

On October 18, 1904, Helen Keller Day was celebrated at the World’s Fair in St. Louis, a seven-month event commemorating the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. While there were hundreds of special days—Kansas Day, Barbers Day, Cuba Day, Apple Day—Keller was the only living individual so honored. Her experiences on that day provide insight not only into her life, but into her times as well. At first glance, the choice of a woman—a young, blind, deaf woman—may seem odd, but a century of perspective shows her to be the perfect choice because of the contradictions and ironies she embodied.

Eager anticipation of her public address at the Fair was typical. Thousands, hungry for a glimpse, awaited her arrival as guards patrolled the building where she was to speak. Frustrated spectators, turned away from the packed auditorium, tried to get a peek through the windows by climbing stepladders. The exposition advertised itself as a university for the common man, and the throng would not be denied.

Keller was 24 years old, recently graduated from Radcliffe, an accomplished “authoress,” a vision of loveliness (but for the left eye, which “looked blind” and which she always turned away from the camera). By 1904, she was considered a model of purity and refinement, a young woman who took life in “through her sensitive hands and the wondrous sympathy of her intellect.” Not yet a suffragette or social reformer, her passion at the time of the Fair was for innocuous generalities— compassion, opportunity and such.

She dressed in a pink and dove-gray linen dress for the occasion, an honor not even bestowed on Missouri’s beloved native son, Mark Twain. One of Keller’s most loyal admirers, Twain was dazzled by her fiery intellect and determination, and considered her Napoleon’s equal in importance to history. She, in turn, found inspiration in his ability to “smite wrong with the lightning of just anger.”

David Francis, president of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company, escorted Keller to the stage. It is more accurate to say that he piloted her, steering her carefully through a boisterous crowd grabbing for a souvenir thread from her cuff or a petal from her flowered hat.

Children from local schools for “the afflicted” sat in the front rows of the auditorium, some deaf boys later reporting that it had been “one of the happiest days in our quiet lives.” Keller was presented with American Beauty roses. Violin solos were played by Lester and Tessie Van Zant, twins who had traveled from the Kansas School for the Blind. When it came time for Keller’s address, she was flush but smiling as she rose to speak.

The first full sentence Helen Keller ever uttered was: It is warm. This simple string of words was the hard-won achievement of lessons with Sarah Fuller begun in March, 1890. The process involved the delicate placement of fingers, the slow movement of tongue and lips. It was tedious, wearisome work, requiring keen focus, unflagging stamina, patience. Only the irresistible urge to make human speech made it bearable.

Keller, a child of the unreconstructed South, equated utterance with the release of a soul from bondage, the freedom to define one’s self unfettered by interpretation. Mouthing words, she soon discovered, was faster than spelling with her hands, and she had a great deal to say. But even after years of practice, her speech was difficult to understand. Frustration became her constant companion.

St. Louis at the turn of the 20th century was a city crowing about progress and growth. The robust language of boosterism and the City Beautiful movement provided distraction from the problems of decline and change. Railroads had stolen traffic from the Mississippi River, formerly the main artery of the nation’s interior. Automobiles and trucks would soon reduce traffic on the rails. The old equilibrium of creoles and Yankees, freedmen and pioneers, robber barons and the industrial poor was gradually being upset by newer waves of immigration from southeastern Europe and from the former Confederacy.

It was a time of displacement and anxiety: tenement squalor, labor strikes, lynchings, a vertiginously volatile business cycle. Danger lurked in every corner, whether in the guise of a desperate slum dweller, a Pinkerton thug or a bomb-wielding anarchist. Paradoxically, it was also a time of great optimism. The reach of public education was rapidly extending. Territorial limits continued to expand. All manner of disease was being eradicated. As the standard of living rose, Americans professed the gospel of uplift, their parlors packed with tokens of bourgeois life: pianos and tea cups, doilies and potted ferns. Middle-class aspirations were fueled equally by faith in self-improvement and a terror of being left behind.

What better way to soothe the nerves of an anxious yet striving public than with a World’s Fair? It would simultaneously calm and spark the masses with a unified vision of harmony and order on a grand scale. Symbolizing progress as an inevitable march west, the 1904 Fair extolled the national virtues of expansion and purchase. As the new age of mass media and mass production dawned, it offered subtle tutelage to the common man in the exercise of his civic duty to consume.

In keenly competitive style, St. Louis created a fair to top all fairs, a spectacle of breathtaking dimensions where the line between entertainment and education melted. For the price of admission, anyone had access to thousands of displays of civilized man and technology, and of savage man in a titillating state of nature.

Keller had attended the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893—the World’s Columbian Exposition—which celebrated the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America. It, too, was an extravagant affair, introducing an entirely new sense of scale for international expositions. On a subtler level, it demonstrated that civic leaders were willing to risk enormous sums of money in the service of trade, even during the Panic of ’93, the most severe economic depression the nation had ever known.

Barely thirteen years old, Keller visited the Chicago Fair with her teacher, Anne Sullivan, and Alexander Graham Bell. She was just becoming something of a celebrity (she would be introduced to Twain the following year) and was granted special permission to touch the exhibits. “I took in the glories of the Fair with my fingers. It was a sort of tangible kaleidoscope.” With Bell as her escort, a good deal of her visit there, not surprisingly, involved the examination of telephones and phonographs, inventions which, in her opinion, were able to “mock space and outrun time.”

If Midwestern cities had any metaphorical value for the national character, it was their sprawl, their vigorous competitiveness and their harried citizens. Chicago had won the bid to host the Fair over many cities, but none felt the sting of losing more deeply than St. Louis, which had outranked Chicago in terms of the nation’s culture and economy. By the end of the 19th century, however, Chicago was leaving St. Louis in the dust. The wounded rival positioned itself for the next opportunity and, when it came, vowed to surpass Chicago’s Fair in every detail.

In addition to lip-reading and vocal culture, Helen Keller had studied the standard subjects—history, geography, arithmetic, algebra, geometry, literature, French and German. As candidate No. 233, she successfully completed the entrance examinations to Radcliffe College and was admitted in the fall of 1900. The scope of her studies broadened to include Elizabethan literature, and the history of philosophy under the tutelage of Josiah Royce.

Her years at Radcliffe, particularly the hectic pace and enormous quantity of texts, had the unexpected effect of ruining the romance of education for her. However, despite the disappointment and frustration, her college experience made her one of the most astute observers of the century unfolding before her. Keller understood what few yet did—that speed comes at the cost of comprehension, that the sheer volume of data often defies order and sense, and that an overtaxed mind loses the capacity for joy. Characterizing knowledge as “the great heart-throbs of humanity through the centuries,” she came to consider “the precious science of patience” an essential component of learning.

Education at its finest would thus be a stroll, a quiet walk with sufficient time to linger and contemplate, not a mad dash from one distraction to the next. Because the 1904 Fair had been designed with ample meditative vistas, a vast range of walkways and reflecting pools, it appeared to be the perfect venue for this sort of education. However, its daunting size and social-engineering agenda quickly overwhelmed visitors, who found themselves growing more and more exhausted the longer they stayed.

In fitting commemoration of the Louisiana Purchase, an act as formative to the nation’s identity as the Constitution, the Fair demonstrated an America enthralled with size for size’s sake. Coincidentally, initial financing for the Fair—$15 million—was the same amount paid for the entire territory, an area that effectively doubled the size of the country overnight. Guidebooks for the well-heeled insisted that a minimum of two weeks was required to do the Fair justice. They warned of the toll it might take on the feeble or high-strung. One newspaper declared that the Fair was a cumulative series of mental shocks. Those with delicate constitutions were admonished to avoid the Pike, the mile-long strip of amusement concessions considered by some to be an outright assault on the senses.

Taking in the Fair became a matter of flying from exhibit to exhibit, buying a souvenir here, taking a snapshot there. A smattering of knowledge was the best a person could hope for, and it had to be acquired quickly because all the Fair structures were slated for imminent demolition. Like other Fairs of the era, it was an ephemeral Eden, built for a season, then razed to the ground. Planned obsolescence was practiced on a grand scale, creating an eerie nostalgia for something still in existence. Many diaries of Fairgoers reveal a sense of loss and longing that they hoped photos and souvenirs would help to assuage.

The typical visitor had neither the money nor the leisure to make much sense of the Fair. There simply was not enough time. Besides, the excess of stimulus was intended as a distraction, an escape from worry. Keller’s complaints about college provide an apt assessment of the Fair. In her opinion, the lack of time to gather one’s thoughts was inherent to the design of higher education and that a person went there “to learn, it seems, not to think.” The rapid ingestion of information from disparate fields encumbered the brain with “a lot of choice bric-a-brac for which there seems to be little use.”

By dedicating a day to Keller, Fair officials had inadvertently chosen to honor the person least able, and most unwilling, to succumb to sensory overload. Her limitations had become instrumental in slowing down experience in order to make sense of it, and to enjoy it. Once again given special permission to touch the exhibits, Keller learned, through deliberate, close-range contact, far more than the harried average visitor. Vision and hearing allow for distance, but touch does not. Keller’s method of learning reduced the separation between observer and observed to a bare minimum.

As she stood to begin her speech, she placed herself carefully before the crowd. They had come not merely to honor her, but to get a look for themselves, to size her up against popular preconceptions ranging from wunderkind to freak of nature. An accomplished young woman, she was already the brunt of a genre of jokes that still bear her name. Consequently, she had begun paying meticulous attention to her posture and placement of hands, and always presented the best side of her face to the audience.

Breathless silence hung in the air as they waited for her to open her mouth, the mouth that had so frustrated and disappointed her now an object of awe to others. She spoke in a low voice, nearly inaudible, with Sullivan subsequently repeating the words for the audience. Keller’s speech began with what was expected of her—serene reflections upon the value of instruction and hard work. But from these vague niceties, she proceeded to an impassioned plea for service to the needy. It was imperative, she insisted, that the strong care for the weak, and that man follow his innate instinct to help. Her remarks closed on a rousing egalitarian note: “God bless the nation that provides education for all her children.”

The crowd rose to its feet; but did she sense the roar of acclaim as she had once felt “the air vibrate and the earth tremble” at Niagara Falls? Leaving the great hall, did she tolerate the hands pawing her as small price to pay for celebrity, for approval instead of disdain for a creature who might as easily have found herself on display elsewhere at the Fair—at the “Education of Defectives” exhibit, perhaps?

After a break for lunch, her itinerary continued at the Philippine Reservation, the most popular attraction at the Fair, so large that it was almost a fair unto itself. In this collection of villages, built from native materials shipped to St. Louis along with the human specimens, dwelled the largest assembly of indigenous peoples ever gathered at an international exhibition.

What sort of education did the common man receive at the Fair? What deep nostalgia stirred in a rapidly segregating city on the border between North and South? What did the future hold for a town whose air was clouded with factory smoke, whose taps delivered water the color of mud, whose crowded tenements were firetraps?

Before the Chicago Fair, America had defined itself by the frontier, a line where wilderness and civilization met. But by 1904, the frontier had been declared closed, and something else was reshaping what it meant to be an American. Despite all the talk about progress and bright prospects, the past had never looked better, especially a romanticized past pointing to the nation’s heroic mission to expand. In this version of history, acquisition of territory was the very definition of progress.

It was fitting to locate the Fair that celebrated the Louisiana Purchase at the western edge of the city, though it took nearly four years to convert two square miles of old growth forest into a meticulous landscape for over 1,500 buildings. The design of the Fair conveyed a sense of triumph, from the mammoth exhibition palaces—Fine Arts, Mines and Metallurgy, Transportation, Education, Electricity—to the casting of statues and naming of streets. Walkways and canals were lined with a mélange of symbols of manifest destiny: explorers and trappers, conquistadors and Crusaders, sod busters and missionaries.

General admission was 50 cents and an average of 100,000 people attended each day. Roughly 15,000 people occupied the grounds—hotel and restaurant workers, police, firefighters and hospital staff. But the most visible of the Fair residents were the 2,000 tribal peoples imported as living ethnological specimens.

On display in various anthropology villages were Native Americans (Sioux, Osage, Pueblo, Cocopa, Kwakiutl, Tehuelche), Pygmies from the Belgian Congo, and Zulus who performed twice a day in the Boer War re-enactment. The majority, however, were Filipinos, who resided for nearly six months at one of the most popular exhibits of the entire Fair.

The Philippine Reservation served several purposes: to display the rich natural resources of the islands so recently taken as spoils of the Spanish-American War; to demonstrate that its inhabitants could be educated and trained in the service of industry; and to drive home the stark, and reassuring, contrast between barbarity and civilization.

In the following decade, Helen Keller would take a poke at the folly of American imperialism, which today resonates as hauntingly prophetic. In the midst of the nation’s frenzied “preparedness effort” for World War I, she would state: “You know the last war we had we quite accidentally picked up some islands in the Pacific Ocean which may some day be the cause of a quarrel between ourselves and Japan. I’d rather drop those islands right now and forget about them than go to war to keep them.”

But in 1904, she was still quite anxious to present herself in the most favorable light. On her day at the Fair, her fondest wish was to visit the Reservation, the pre-Disney equivalent of exotic entertainment.

Forty-seven acres, separated from the main grounds by Arrowhead Lake, were given over to the Philippine exhibit. Visitor access was provided by a bridge that led to a full-size reproduction of the entrance to the ancient walled city of Manila. Every detail, from its locale at the far edge of the grounds to the layout of the tribal villages, announced that the Reservation was an uncivilized place, the very antithesis of progress. Unlike the manicured setting for neo-classical exhibition palaces, the Reservation was not landscaped. It was thickly wooded, the buildings primitive, the people inside choreographed to appear savage and strange. Militia units encamped on its perimeter.

Although there were plenty of westernized Filipinos at the exhibit (Christianized Visayans, for example), the “wild tribes” were the big attraction—the Igorots, Negritos, Bagabos and Moros. They performed mundane functions, ceremonial dances and spear-throwing competitions at regular intervals throughout the day, ostensibly conducting their normal lives under the relentless gaze of Fairgoers. Their gestures, foods and habits became fodder for newspaper copy; yet nothing captured the popular imagination more than the controversy over their clothing.

In the matter of native garb, authenticity came into fierce conflict with Victorian notions of modesty. Filipino natives were given fedoras and overcoats to wear over their loin cloths and sarongs, until the debate became so absurd that efforts to conceal their flesh were abandoned. By winter, however, the problem arose again. Scantily clothed, living in tropical dwellings, the Filipinos had little protection from the cold. Small heaters were finally installed in their huts, but this prompted spectators to throw rocks to flush the natives out. Irate ticket-holders, who had paid the extra admission fee, felt entitled to see nearly naked savages no matter what the weather.

Datto Bulon, Bagobo chief

October 18 was fair and mild. Upon the guest of honor’s arrival at the Reservation, a group of Igorots performed a ritual dance outdoors, Sullivan narrating to her pupil their intricate steps. Keller then wandered for a while, examining skulls hung from totem poles, fingering brass bracelets on women’s arms, climbing a ladder into a tree house. Because she was scheduled for a reception that evening in the Missouri Building (an elegant, costly structure that would burn to the ground the following month), she needed to rest after all the excitement. Before she could leave, however, a Bagabo prince named Bulon stepped into her path.

Keller’s manner of learning, like her singular life, was a juggling act of contradictions, a blend of disciplined patience and fierce hungers. A spirited child, she often grew enraged with desperation, frustrated in her attempts to express the tumult of her ideas and feelings. But language, received and delivered through the hands, opened the door to a life beyond physical limitations and convinced her that knowledge was better characterized as a series of heart-throbs than as a bric-a-brac pile of information.

Now, the freshly-minted college graduate found her path blocked by a tribal prince, a young man about her age with a full mouth and broad brow. Photographs of Bulon at the Fair show him in traditional garb—knee pants, cropped jacket embroidered with shells and beads—often wearing a cloth cap, though occasionally with his hair cascading beyond his waist, clearly an object of lavish care. Such images allow us some sense of the heft and texture of what he presented Keller as a sign of welcome and respect. After formal introductions, he offered her the full sweep of his hair, allowing her to feel it with one hand while she described to her teacher a delight beyond imagination with the other.

0 Comments