Praying, or Not, in the Stacks

I’m enjoying writing these disjointed digressive essays, following my thoughts as if pursuing Diderot’s lovely and lively pixies as they flit from one succulent subject to the other. As a matter of fact, my essays are so écriture automatique they should not be called essays, although, truth be told, the first composer of essays, Montaigne, concomitantly created an individually side-tracking style that deviates and strays from one idea to another and then back again. His was a wild and exuberant mind, and he was so well read that he couldn’t help many of the internal collisions of ideas inside his cornucopian intellect, and it was the results of these happy collisions that he would jot down. I don’t know what my excuse is, for I have a wild but entangled mind, like a plot of impenetrable jungle where vines entwine among the trees and rambling briers tangle along coiled roots. It’s so hard to traverse my terrain that I want to climb straight up into the canopy to see the blue sky, sorta like Pontus de Tyard, member of the Renaissance Pléïade poets, who in his Solitaire premier, ou Discours des Muses & de la fureur poétique, mentions that the poet climbs knowledge like a mountain to the heavens: the more he reads, the more he climbs, the more his horizons expand, but the successful ascent is by no means guaranteed, and for those who do perservere, the climb to the top can take numerous diverse paths.

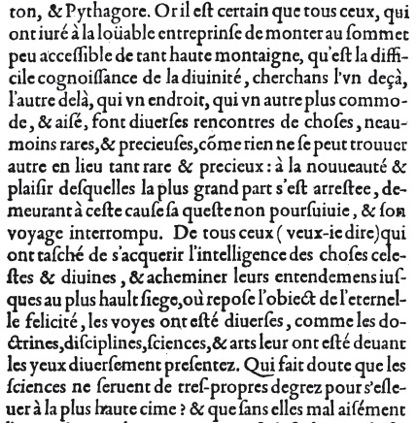

«L’ame purifiee [est conduite] en reuerente admiration de la non iamais comprin∫e imme∫urable grandeur de la ∫our∫e de bonté, beauté & ∫apience de l’vnique Soleil diuin, ∫elon Platon, & Pythagore. Or il e∫t certain que tous ceux, qui on iuré à la loüable entreprin∫e de monter au ∫ommet peu acce∫∫ible de tant haute montaigne, qu’e∫t la difficile cognoi∫∫ance de la diuinité, chechans l’vn deçà, l’autre delà, qui vn endroit, qui vn autre plus commode, & aisé, font diver∫es rencontres de cho∫es, neaumoins rares, & precieu∫es, cõme rien ne ∫e peut trouuer autre en lieu tant rare & precieux: à la nouueauté & plaisir de∫quelles la plus grand part s’e∫st arre∫tee, demeurant à ce∫te cau∫e ∫a que∫te non pour∫uiuie, & ∫on voyage interrompu. De tous ceux (veux-ie dire) qui ont ta∫ché de s’acquerir l’intelligence des cho∫es cele∫tes & diuines, & acheminer leurs entendemens iu∫ques au plus haut ∫iege, où repo∫e l‘obiect de l’eternelle felicité, les voyes ont e∫té diuer∫es, comme les doctrines, di∫ciplines, ∫ciences, & arts leur ont e∫té deuant les yeux diuer∫ement pre∫entez. Qui fait doute que les ∫ciences ne ∫eruent de tre∫-propres degrez pour s’e∫leuer à la plus haute cime?»

“The purified soul [is lead] in reverent admiration of the grandeur of the immeasureable but often misunderstood source of goodness, beauty and knowledge that is the divine Sun, according to Plato & Pythagoras. Now, it is certain that all those who have sworn to the laudable entreprise of climbing to the almost unaccessible summit of such a high mountain, wherein lies the difficult knowledge of divinity, they search this way or that, at one place or at another easier one, making diverse discoveries of things, however rare & precious, since nothing else can be found in such a rare and precious site: because of the novelty & pleasure of such finds most people halted their movement, their quest no longer pursued, their voyage interrupted. For all those (I mean) who tried to acquire the intelligence of celestial & divine things, & who wished to direct their comprehension all the way to the highest degree, where the object of eternal felicity reposes, the paths have been diverse, just like the doctrines, disciplines, sciences and arts were presented to their eyes in diverse fashion. Who doubts that the sciences serve as very proper steps to raise oneself to the highest peak?”

Pontus de Tyard gives me the permission to wend my way to the top, and to guide you, if you wish to follow, along unique topography, always going up, to see better, to see more, and to see new things.

So far in this «News from the Stacks» series, I’ve written about sex and violence, so I’m not sure if Pontus de Tyard would find that my horizons are well expanded. Still, as I am living in the United States of America, I might as well mention religion. Funny, religion plays such a small part in people’s daily lives in other countries where I’ve traveled, like France, Canada, Iceland, even Spain. Perhaps those populations don’t like to talk about it. But in these United States people love to talk about religion, they yell it from the rooftops, from the streets, with megaphones. In this country, religion rears its hurdle of a head so often that it becomes a stumbling block, and one trips over it time and time again. It is part of the culture to ask each other about our beliefs, in part so that the believers out there know friend from foe. I think we should reconsider rechristening our country as the Ununited States of America, but still manage to keep the same old USA moniker. Religion, in this country, separates us, and is used blatantly as an axe of division. I was under the impression that religion was suppposed to be something oh so personal. I was also under the impression that religion was supposed to keep its hands off the levers and steering wheels of our political system, or so thought our foundering fathers, excuse me, our founding fathers. Please, don’t tell me how religious they were as a bunch, or how Christian, for in a group of ten foundering fathers you will uncover ten different modes of religious thinking. Our forefathers, not to forget our foremothers, ran the gamut of Quakers to atheists. Why certain people today should place more importance on one religious group over the other is their own predilection, and should not be forced on the rest of us. Because there is, indeed, the rest of us.

Please remember that Montaigne was also writing during a period of religious strife and uncertainty, when Christians were murdering Christians, as if each adversary were taking directions from Christ himself to go out and annihilate their neighbors. “Turn the other cheek” was hardly heard; “Slit the other’s throat” was more in tune with events.

Here in our cozy bookstore on the Florida seacoast (please don’t attempt to identify us: Florida has 2,170 km (1,350 mi) of coastline, even if it is receding), where a handful of us play every day at finding each book a reader, we construe religion in five different ways.

Cassandra, our intrepid mistress, as her name implies, has seen—and communicated with—spirits from a dimension different from our own, who impart to her verifiably correct knowledge that she could not have discovered on her own. She reveres Nature as the goddess she is, and truly there has never been anyone greener than our boss: we recycle everything; I even mulch the coffee grounds in my garden. The blood of Rousseau, of Linnaeus, of Thoreau runs through Cassandra’s arteries, and she reads and re-reads Balzac, Zola and Dickens in order to witness the battles between humans and Nature, as human nature tries to bring the goddess down into the muck men have created, as if to control her and possess her in chains. Stupid man! He controls and owns nothing! His festering societies exude a thermodynamic miasma that succeed only in bringing his own doom. The goddess observes society’s collapse from afar, patient, vigorous, self-renewing, knowing, with the wisdom of Athena and the passion of Venus, that her beauty and vitality will outlive mankind’s parasitic histrionics as he outlandishly truncates his species’ own lifespan, amassing gold and diamonds but in the process contaminating his drinking water.

Young Max tends to believe in the Occult, is an avid reader of it, and is now trying to decipher ancient runes for the wisdom they contain. (When I was his age, it was Hermes Trismegistus whom I was after, trying to decipher his conveniently hermetically-sealed sacred texts.) Archaic religions hold his attention, for their polytheism in which each God is answerable to each element of creation, starting with the God of the Sun, who may, or may not, be named Helios. Monotheists miss the point, that the energy of animism is boundless, that the individual deities are but metaphorical fragments of a diverse Creation, but which symbolize that every element of that Creation is infused with a constant state of flux. Diana and Poseidon and Vulcan; Silvanus, Faunus, Pan (my personal favorite is Dionysus/Bacchus), in all their embodiments and in all their manifestations hold sway over men, and men should do well by naming them one by one and, remembering their influence on human affairs, at the very least light votives for them every once in a blue Selene. (Here in Florida we should appease the deities of the four winds, Boreas, Eurus, Notus and Zephyrus, to quell their furor and pass us by in times of atmospheric disturbances.) In a similar vein, Max holds a candle out to vaster Gods, those of the universe beyond our piddling little earth, through Astrology which observes and measures the government of planets and stars on our destinies. It is not by accident that the Renaissance poets were also enthralled by the movement of faraway heavenly bodies, straining to hear the Music of the Spheres as gigantic orbs crossed paths and spiral nebulae spun stardust that, with violent agitations managed to knock carbon and potassium and dihydrogen monoxide into us.

Bob keeps his religious cards close to his chest. I’ve asked the others if anyone has heard him say a peep about his beliefs, but apparently he’s had no interest in revealing this dimension of his life. Perhaps he is an agnostic, preferring to profess no adamant spiritual convictions. Or maybe he is a secret adherent of Santería, and has learned that he makes fewer waves in daily life if he leaves his credo under wraps. I’ve never seen him wear white, however. How crazy, to have to wear white!

Marie is a different story. Her religious life is an explosion of tentatives into the intangible, the transcendent, the ethereal. But a circumstance in her life must be mentioned beforehand: she lives, in intimate physical contact, with her Catholic-monster conscience, an overbearing Jabberwock who delivers daily the Word, and sententiously interprets from on high the Law and the Rules, the Needs and the Musts, the Have to’s and the Oughts, the Instructions, Directives, Regulations, Commands and all the Decrees, that come straight from the Dogma of the Roman Catholic Church, including secondary and tertiary edicts, mandates and dicta. Her living conscience is her mother, a beautiful and elegant lady, who walks through the house wafting behind her the scent of incense. Marie has had to possess a vigorous and determined mind, an autonomous attitude, and an intensely passionate will, not to be crushed like a martyr under tons of churchy debris. When Marie was younger, her imperiously religious mother pushed her into the embrace of the Wiccans, and for twenty years the recalcitrant daughter remained staunch in her entrenched defiance: how more polar could the opposite be? But she loved the rituals, which ideally took place out in Nature, as opposed to some man-made edifice. One Halloween, however, as Marie tried to follow her observance inside a locked bathroom, her mother howled outside banging on the door, beseeching her to abandon Satan and his wicked ways. Her mother would find her Wiccan books and throw them out, but Marie would go out and repurchase them. She once had to face her mother and godmother who had conspired together to sic a priest on her. The priest placed both hands on her head while he intoned incantations to rid her of the Beast. But she would not come back into the fold. She held fast to her intuition, which told her to get as far as she could from the Church of Rome. Even Nature conspired to give Marie an aspect of the iconoclast exotic: starting at her hairline in the middle of her forehead, in a sort of modified widow’s peak, a birthmark of pure white runs above her scalp for a few centimeters, giving rise to a streak of white in the very center of her head of auburn hair. I much prefer the Spanish word for birthmark, lunar, for it definitely displays the hand of Selene, lunar goddess. This strikingly beautiful “lunarmark” was inherited by her daughter, and by her granddaughter, embracing a straight lineage of gorgeous descendants who just by themselves configure a Wiccan coven. Marie’s outraged mother would accept none of this, not the look, not the practice, not the purported beliefs, and she reacted by becoming a Harpy straight from Hades, berating her daughter violently and flinging doctrine on her like Jehova rained brimstone and fire onto Gomorrah and Sodom. Marie’s suffering became so intolerable, that in entries to her diary of that time her mother makes appearances as “The Inquisition.” It was as if Torquemada himself had descended from Heaven (I assume the Church turned Her inquisitive soldier into some sort of Saint or Semi-Angel, for all those souls he saved) and lent his wrath to a little old lady who wanted her daughter to come back to Catholicism. Time quelled both Marie’s disposition for Wicca and her mother’s tyrannical persecution. Again they live in the same house, the mother still spewing Catholic dogma, the daughter still fending it off.

Finally there’s me. I was also born into a Catholic family, but one not so conservative. My parents told their children that later in life, when we were old enough, we would be able to chose, independently for ourselves, our profession, our mate, and our religion. Still, they would have wanted me to be an architect (I chose college professor), a mate of a different sex (I preferred not to stray that far from my own), and, I imagine, they would have selected for my spiritual pleasure some type of old time religion, to make me love everybody. I don’t think they were very happy when I chose no religion at all. Yet, Pan bless them, they never criticized!

Atheism was, to me, the only stance possible after exponentially diminishing returns. Viewing that mighty worldwide array of spiritual options, wandering from one denomination to the other, I was overwhelmed with the multitudinousness of them. In Florida we are blessed because we seem to have the full complement of world religions all at our doorstep, literally, as I almost jogged onto the severed head of a pig ceremoniously set on the ground by a Santero who wished to protect his newly-purchased acreage which abutted, unfortunately, on mine. Wandering led to wondering, and before I knew it, I could not abandon one set of rules in order to acquire others that seemed just as arbitrary, just as eccentric, just as implausible. And frankly, just as pointless. It was easier to drop all the rules, the rules of religion, mind you, not the rules of morality. Many fervent believers are so ignorant that they confuse the two, thinking that we atheists lead wild and frenzied lives devoid of ethics, beholden only to Bacchus and Pan, luridly espousing debauchery and pandemonium, searching only for pleasure and sybaritic extravagance. Although, now that I’ve written it down, it does seem alluring, don’t it? Fear not, my bacchanals are over, and have dwindled down to a few solitary sips of absinthe, in an effort to have the Green Fairy entice my Muse to hang around for a while. Perhaps I’m not such an obdurate old atheist after all: I believe in my goddess, the Muse, Euterpe, who infuses me with the pleasure of writing, cajoles me with the secrets of the universe, and who, when she is enamored of me, allows me to hear the Music of the Spheres, a melody much greater than my own existence, vaster than my own domain, wiser than my own imaginings. This is an ancient old-time religion I can live with.

∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫∫

In spite of my wandering away from the Church of my fathers, I could never relinquish my predilection for Fallen Angels. I call them Fallen Angels for they once aspired to be angels, helping humanity in any way they could, yet at a particular moment in their lives they felt they had to fall back from such mighty ambitions. As they fell, or after they had fallen, they received the backlash of the laity, who dared to criticize their decision, accusing them of ingratitude, selfishness, even treason. My heart goes out to them, for who is the laity to judge them? But this essay is fast exceeding its word allotment. I kindly pray that you continue to the next essay on the subject my proclivity for lapsed ecclesiastics.

0 Comments