The Keeping of Chickens

I am aware that contributors to this part of the Solution Hole Press dot com Internet site should stick close to the heart of the matter, the solution hole metaphor, but I want to speak about a matter of the heart—keeping chickens in my back yard—and, I promise, I will somehow make it relevant to yous who believe in the analogy of the hole in the ground where disagreeable voices from society have been swept away and kept mute under piles of debris so that they’re no longer heard by future generations. Lost voices, I was told, speak about ousted art, forgotten maestros/maestras, silenced messages, eliminated intellects. “Remember Giordano Bruno!” I was told, who was burned at the stake for heretical publications having to do with the plurality of worlds as well as the divinity of Christ. Well, that was in 1600, my friends, in 1600. If I know yous guys you’re like me, I confuse the 17th Century with the 18th, I telescope biographies so that Montaigne and Montesquieu were contemporaries, the Enlightenment came just after the Middle Ages—which makes so much sense!—and Nostradamus is a shining star no matter in what century he lived. Well, I just looked him up, and it’s 1503 to 1566, so that’s the Renaissance, right? The Re-Birth of thinking, the Reformation, the strategic Regrouping, the Real Pain in the Ass that got the whole world thinking about what was right about the Catholic Church that had enjoyed centuries of monopoly until then, but also the opposite, what was wrong with it, which apparently was legion. Giordano Bruno, for instance, doubted the quintessentially Catholic invention of Transubstantiation. Other people went to their doom because they also doubted it, the big T, the big bad T, with a capital T and that spells Trouble. The fact of the matter is this: the bread (these days it’s a wafer and it tastes like cereal) and wine (which in most Catholic churches in the world that I’ve been to dispense with for the Communers; only the priest consumes it) used in Communion are changed, inexplicably, mysteriously, into the body and blood of Christ. Why Medieval ecclesiastics came up with this wacko idea is beyond my comprehension. A quick dip in the Internet tells me that it was Hidebert de Lavardin, archbishop of Tours, who was the first to come up with this gonzo innovation, in the 11th Century! As far as Catholic ideas go, this is a late one, and extremely far removed from the actual teachings of Jesus Christ. In other words, the concept is as arbitrary as they come, and it eventually became sacrosanct, with accompanying autocratic corollaries: believe in this or else…! Still, while the idea of Transubstantiation makes me gag, since in effect, the priest partaking of this feast becomes a cannibal, my mind finds it difficult to go into a separate direction from my senses: the host, to my eyes, remains a wafer, the wine does not change in color or taste. I don’t think I would go as far as actually drinking it; my nose would detect blood way before my tongue would.

So, despite what the senses say, the Catholic Church maintains its policy on Transubstantiation, not as a metaphor, not as a symbol or even an analogy (consuming the host and wine as if you were consuming the body and blood of Christ), but as a real and true alchemy that sees the metamorphosis of the Eucharist bread and wine into flesh and blood. Mr. Pope, monsenior Pope, Vicar of Christ or Vicarious Christi, or whatever the heck your title is, this certainly means Trouble. Why, you ask? Well, how many of them Catholics out there actually believe this still? Are they really eating the body of Christ? If they don’t believe it, then they are heretics, and they should meet the same fate as Giordano Bruno. But I doubt we need to worry, if the Church wanted to pursue all the heretics out there, the red-faced cardinals would be very, very busy, and deep down I think that they know they would end up with hardly anybody in Church on Sundays. What a church that would kill all the disbelievers out in the pews! Americans, especially, would be bothered, because they’re used to shopping for churches the way they shop for anything else. For convenience. There are masses throughout the day and night, in multiple languages, sometimes even reverting to the original Latin, for the enjoyment of those who wish to understand absolutely nothing. Some masses are accompanied by guitar and tambourine. Some of them are so boisterous and euphoric that they might as well be Protestant rites. There is always something for everyone. Religion has joined the ranks of consumerism, with ease of attendance, after breakfast or before dinner, with or without music, or Latin, but always, always with the famous bread and wine.

However, if the consumers ran the risk of being burned at the stake they would most likely flock away from that church.

“Come to church with me this Sunday?”

“Nah, I don’t think so. They burned my neighbors there last week, and a second-cousin.”

“Oy vey! They shoulda went to a different church!”

Um, just in case the Church takes a violent stance against this article that I’m writing here, I’ve taken the precaution of using a pseudonym in my byline, like a nom de guerre. Yous guys who know the penchant for anagrams during the Renaissance might be able to figure it out. Ask Alcofribas Nasier.

So what does all this have to do with keeping chickens in my back yard, and what do chickens have to do with the solution hole full of forgotten voices from the past?

I am one of Cassandra’s volunteers in her bookshop in Key Largo—not her real name, not her real place—but I wish it were! I have been working here at Braund’s two or three days a week for the past two years, ever since I retired. I do it for the love of books and to help Cassandra out who was all alone in the deluge of books that streams in just about every day through her front door. She explains that when economic times are bad, people tend to sell their books. She’s owned this bookstore for a few economic cycles (since Reagan, I think), so she knows what she’s talking about. Well, I’ve also noticed recently that an awful lot of people have been passing on and leaving whole libraries behind. When a whole library shows up in the shop we go on overdrive because we need to inspect, process, describe and evaluate hundreds of books in a few days. Then Cassandra places all this information online on her website, so that we may quickly find new homes for these orphaned books. Every once in a while, a book comes my way that strikes my fancy, and Cassandra allows me to purchase it even before it has an online presence. Such a book, or books, in this case, came to me last year.

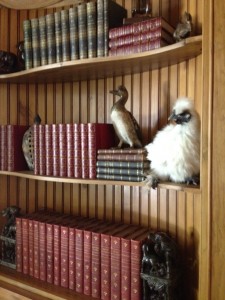

Four volumes, to be exact, looking so worn they look older than their years, published from 1909 to 1912 in Scranton by the International Textbook Company for the ICS, that is, the International Correspondance School which originally had published the material in booklet form that was sent piecemeal to their students. This collective edition was to facilitate the work of students who enrolled in more than one course. The books maintain the order of individually numbered fascicles, ranging from 7 to 11 in each book, none of which seems to have more than 49 pages. At the end of each tome there are examination questions, 20 for each section, that could potentially be asked in the final exam. My copies are well-used, home-hospitalized with three to four horizontal bands of clear tape across each whole book, plus a vertical one to protect the spines, giving the dark brown covers a glossy sheen. All four volumes show water damage to the outside edges of the four corners, penetrating up to the first 8 pages, as if the books had been set down on a wet surface, or if they had accompanied the reader numerous times to the place of study in the snow, the place of study being the chicken coop. Ugly as their façades are, it is inside where these books shine. Poultry Farming, in 2 vols., and Standard-Bred Poultry, also in 2 vols., are chockablock with the most useful information, the deepest arcana, the most detailed instruction in both the raising of poultry and the history of the different breeds of chickens. Nothing modern that I had ever seen even comes close to the amount and quality of information as that included in the ICS books. The writing is spare, clear, organized. Unfortunately, the writer(s) remain anonymous, for I see no mention of them anywhere. However, in the copyright page there is a clue as to the possible nationality of the writer(s): after the date of publication of each fascicle, there is an added line stating, “Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London.” A quick fling into the Internet, though, uncovers Stationers’ Hall as an early method of copyrighting books in the English language, so the writers of my books, it seems, might have been American after all.

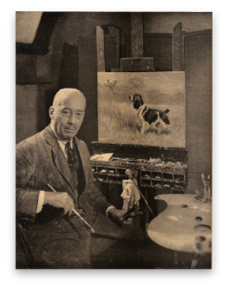

We have more luck with the illustrator of the books. Adding visual beauty to these four volumes are the numerous illustrations of the different breeds of fowl. Too-many-to-count black and white illustrations and lovely full-page color paintings dot the books. The artist signed and dated his paintings: Edwin Megargee, 1911 and 1912. Another fling into the Internet hits paydirt: an American artist from Pennsylvania, 1883-1958, Megargee is known for having done portraits of pure-bred dogs, including, famously, the greyhound logo for Greyhound Bus. He preferred to work with posed live animals, which was fine for most of them, but a champion bull once came close to prematurely ending his career. His gig for the Scranton International Textbook Company led to other portrait commissions of livestock and Megargee found that his sensible, meticulous style was in great demand.

When these books fell into my domain, I knew that I was going to go out and get myself some chickens. The magic of the fowl, the mystery of their origins, the exoticism of the various far-flung breeds, proved too much and I could not resist. After much study, and after much debate with myself, I decided on all bantams, since they are smaller, mostly of the Cochin and Silky breeds, from China and India, respectively. I ended up with 28 tiny chicks called White Frizzles, Black Frizzles, Golden Laced Cochins, and Golden Sebrights. Also, the hatchery must have made a mistake because I ended up with a Light Brahma rooster, which I did not order. He has turned out to be the most beautiful one of them all. I raised the brood in one of my shower stalls, with heat lamp and medicated chick starter and Mozart playing in the background. I would play with them as often as I could, and invited friends and nieces to come and play with them as well. The result is that they are tame, they come running when it’s time for tidbits, and the hens have just started to lay eggs, right on time, on the fifth month.

Since I live in the city, all of the roosters, 14 of them (nature was exact here in its male-to-female ratio), and the more voluble female cacklers went to a friend’s farm in the country, about an hour away. The flock I’ve kept are all quiet, sedate and sensible hens, who know where to lay their eggs, where to roost, and how to keep their squabbles to a minimum.

Well, you’d think that I had run amok, busted a gasket or gone completely bonkers, for the reaction among various people was very curious. My friends, of course, know me as a person who throws himself into whimsies of every color, and they are tolerant, even if bemused. But others, who shall remain nameless here, remained cool and reticent, with an undercurrent of embarrassment and even contempt. I realized they were being judgmental about my keeping chickens in the back yard! Might they be so urbane and sophisticated that they felt owning chickens was beneath them, and beneath anyone with whom they associated? Could it be that their idea of what is couth and cosmopolitan precludes them from stooping to rustic hillbilly practices? What a world, I thought, where people turn up their noses at something that is ancient and natural and coherent! My friend David, who lives on the farm that inherited all my roosters, grew up in a sparsely populated area of Guatemala, in the jungle near Tikal. He understands me so well, and he derides my critics, saying that it is those who eat fresh vegetables harvested that very day and who collect the eggs that very morning to use in their breakfast omelettes and who, yes, butcher their own chickens that have lived their lives free of cages and have only eaten bugs and grass and not processed meal, those people know what natural and healthy food is all about. City dwellers who feel disdain for us and ridicule those “foreigners” who grow their own bananas and papayas don’t know that they do themselves a great disfavor. By opting for their sophisticated shopping in stores where products are rendered sterile and parceled under plastic they remove themselves from the world of what is natural and healthy.

This world has a name: it is Arcadia, the one in Ancient Greece, home of Pan, the satyr God of nature who ran through its sylvan forests and glens playing his rustic flute, dedicating paeans to his peaceful realm and mischievously looking for damsels to seduce. It is the Arcadia of Astrée, placid pastoral home of a shepherdess and her shepherd mate Céladon, living their episodes of love and passion through the pages of d’Urfé’s monolithic 17th-Century novel, l’Astrée, which makes the Hunger Games trilogy look like a short story by comparison. It is the savage state of nature, our previous home that beckons to us still, the one described nostalgically by Rousseau who blames civilization for having corrupted humanity, of having taken us away from a state of grace in order to live desperate lives of decadence, too distant, spatially and chronologically, from that first home long ago where wholesomeness, virtue and simplicity would soothe our ills, if only we were intelligent enough to go back to it. But others have gone back to it, and tried to take the rest of us along for the ride. For Arcadia runs through the art of Poussin, Fragonard and Watteau, through the music of Rameau into the Music of Nature, through Thoreau’s Walden and right into our kitchens, beckoning some of us to return to our ancestral home, making us plan our vacations (in part) to visit unspoiled landscapes of alpine meadows and deserted terrain, sending us to libraries in order to nurture our souls by imagining bucolic utopias of the past. It makes us run into the solution hole of art and history, like the passionate archeologists that we are, to seek clues, to piece them together, to run our fingers through the muck of the past, so that we may translate those bits and pieces and perhaps use them again in our 21st-Century lives, to soothe our embattled human nature, to find the balm of peace and consolation. Pan knows that we need it. Pan bless us all.

Sadly, many are impervious to the call of the Walden wild and its beauties. They vacation in vast anonymous cities where the slabs of concrete and the overcrowded glass vanquish the last vestiges of Arcadia. It is these people, and they know who they are, whom I beseech to please leave us alone, and don’t belittle us, those of us who seek Arcadia in our own, small ways. It is to them that I raise my glass of wine and wish them good health, as I sit down to eat my frittata made from the fresh eggs of my hens, sprinkled with the herbs I grow in my cottage garden, and I thank my hens Henrietta, Crossbeak, Pixie, Trixie, Blanche, Greyflake, Slate, Suzie and Paloma.

Now, if I could only keep a she-goat to make my own cheese. Chèvre would go so well in a frittata.

0 Comments