The Solutionists: Quest for Immortality, or, the Importance of Posterity

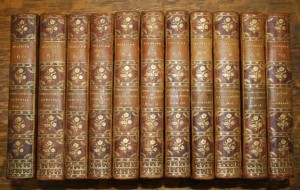

Yet, for all that, take a stroll down bookstore shelves anywhere in the U.S. today and you realize that all of Voltaire, all of his passion, all of his fervor, and all of his catholic interests, have been boiled down, simmered and condensed, concentrated and consolidated, down, down, all the way down to a single, slim book. This reduction saddens the heart, especially when one remembers the number of cauldrons, of stew pots and of sauce pans that Voltaire always kept stirring up. True, this one thin book of Candide may exist in several editions, some admirable, a few with really very nice illustrations, but to know that the rest of Voltaire—his myriad of concerns and fears, his encyclopedic knowledge which encompassed the world and, indeed, through his love of Newton, shot out into the universe—I repeat, to know that the rest of Voltaire is not readily available to new readers is to me such a bitter disillusionment. Where are his writings on India, where he accuses the rapacious Europeans of the despoliation of that huge and wondrous land and of the overthrow of its people, whom he described as the most humane people on earth and morally our superiors because they had learned to live in peace? Where is his history of Charles XII, king of Sweden, whose story he tells for posterity, and for future kings to read so that they may be forevermore “cured of the madness of conquest”? Where is his poetry? Where are those verses he wrote about Joan of Arc, military heroine and celestial saint, especially the part where the Virgin of Orleans wakes up very early in her tent while her vast army bivouacs around her, only to find her donkey in there, with her, in her bed, under her sheets, braying sweet nothings into her ear? Where are his plays? Where the hell are Voltaire’s plays? In his own lifetime he was best admired for his plays. It was his tragedy Œdipus that catapulted him to fame at the age of 22, and every year or two after that, until he was 78 years young and even the year after he was dead, he both hugely satisfied his audience with a new play, and left them thirsting for more.

And tell me, where are his exposés, those scathing reports in which reason and logic come to the rescue of the unfortunates who were victimized by that double-headed beast whom Voltaire had vowed throughout all his life to slay? Calas, Sirven, La Barre come to mind, innocents who were tortured, convicted, executed, by an entrenched system too strong to overturn. One of the monster’s heads was the monarch who with one stroke of the pen could send people to molder in the Bastille, a despot in charge of an aristocracy where the elite purchased their positions with money as opposed to obtaining them through merit; the other head was the ignominious, hypocritical Catholic Church, you know, the one who pardoned Galileo in 1992, the very one who admitted in 2007 that Limbo had, in fact, been a hoax. Okay, I made that one up, but the closest the priests could come to an apology for having used Limbo as blackmail upon their faithful was to say mildly that it was not, please excuse, of revelation born. So after centuries of the fearmongers scaring the hell out of parents who agonized about their dead unbaptized children ending up in Limbo instead of being saved for heaven, Limbo, along with Weapons of Mass Destruction, has joined the millions of lies that the powerful push onto the credulous. Such was his loathing of that monarchical/ecclesiastical two-headed beast that Voltaire automatically appended his signature with the motto: «Écrasez l’Infâme», Crush the Despicable, Squash the Odious, Overcome the Treacherous. No wonder the Revolutionaries’ bloodlust did not cool until they had separated the heads of both their king and the nation’s priests from their bodies.

Voltaire’s legacy might still be apparent today, his voice still audible as it echoes down the tunnels of time, but his books are no longer with us, and the new generations will find it all the harder to return to the source of that voice.

All artists are careful about what they leave for posterity. In the case of the Medieval poet François Villon, he hands down to us his Testament, along with the bequests contained therein, laughing at us when he confers to us noble ideas on life and death, but also his underwear, which do not seem to have lasted as long as his verse. (Voltaire’s brain lasted longer than Villon’s underwear: it disappears from the historical record in 1875, after having bopped around in a pharmaceutical jar for 97 years. Voltaire’s heart still exists, in an urn at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.) In the case of the Renaissance poets of the Pléïade, Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay and five of their closest friends, they, too, left us with everlasting works of poetry. Each of the seven poets in the group wrote several collections of sonnets, odes and elegies, but their leader Ronsard’s celestial metaphor counts as legacy, too. These stars will remind the enlightened ages that the artists who borrowed these heavenly lights as their symbol were thinking of their own illumination, of their own brilliance. They wished to bring the light of knowledge to their society and sustain the struggle against the darkness of ignorance. They fought to bring luster to their poor language and raise it to the standards of ancient Greek and Latin, the bright lights of literature and rhetoric. An earlier group of seven Greek poets had already been named the Pleiades, but that is proof of what the Renaissance poets did best: borrow from a previous age, scour away the rust, and polish things up for a new age. Their symbol, the Seven Sisters in the constellation of Taurus, lost none of their luster when modern astronomers informed us that they were composed of a star cluster of especially luminous blue stars. Knowing that they’re between 391 and 456 light years away and that their nebulosity stems from interstellar dust does not detract from their beauty and poetry. Their splendor will last until, well, until the stars all burn away.

Still, a sturdy metaphor used to identify a group of artists does not necessarily need to be that enduring. It can be surprisingly fleeting. Imagine, if you have the time, the image created in 1924 by André Breton, the leader of the Surrealists, of the “Poisson Soluble”, the Soluble Fish, or the Dissolvable Fish, if you will. How long do you think such a fish would last? It makes me want to wax poetic about it: Would that this flounder be/Quite soluble in the sea/Like ink in water, but/Still, just for the halibut.) But let’s be serious, like the Surrealists.

In his Surrealist Manifesto, where he defines and delineates his movement, Breton rages against the overpowering oppression of the bourgeoisie, against the stagnation of conventionality that asphyxiates the imagination, against the judgmental meanness which waterlogs the lightness of creation, and engulfs in murk the light of art. Art, when it is free, when it is created without hindrance to the imagination, when it cares not a whit for commercial crassness, exalts its creator. For art to thrive in a world of lucre is as oxymoronic as a dissolvable fish. Breton’s ichthyological metaphor disappears in a liquid cloud of colors, and the polyglot mute, unable to describe what he saw, sadly turns away.

The metaphor that we choose for ourselves, this small group of us who live in South Florida and move in and out of these fields of literature and art (and music, too!), those of us who are researchers and interpreters and teachers, but mostly readers, and who wish to disseminate to a wider audience the works of the past, is that of the solution hole. South Florida is pockmarked with solution holes. The Yucatan, too, on the other side of the cataclysmic meteor hit—the one that blew the Cretaceous out of geohistory—where the earth is riddled with them, although there they are called cenotes. In both of those places, our ground is limestone, porous oolitic rock made of innumerable generations of marine life that died and settled on the bottom of the ocean. But when the sea sinks, the earth rises, and after the aeons of rains thundering down and hurricanes sweeping past, after time itself has eroded the limestone on which our civilization temporarily sits, some of the limestone gives in, gives out, gives up. Erroneously called sinkholes, which are different (time for only one dissimilarity: sinkholes can appear overnight), these openings into the past may sometimes hold archeological curiosities, such as sacrificial victims to the Mayan gods, or just the ritual jade amulets and gold scapulars left behind, or perhaps telltale debris from previous generations, like careless time capsules dotting the landscape. They can also be the receptacle of construction trash from when your own house was built in the fifties, like the solution hole in my back yard in Princeton, Florida: it contains mostly detritus, but rummaging through the broken cement blocks I once found a tiny packet encased in the careful folds of a dress, blanched bones still strong, a small skull with fangs forever bared.

So the limestone is the solute, and the water the solvent, and a solution hole in the ground is too good to waste. As a metaphor, I mean. It solves our problem doubly: we muck about in the debris of history, searching for treasures that may still amaze; it also stiffens our resolve in not allowing the art of the past to dissolve into nothingness, and not just because of Santayana’s foreboding augur that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to relive it.” We also give thought to our own testament that we need to bequeath to the future, and I don’t necessarily mean works of our own creation, although they too have a place in our purpose. I speak more of the legacy that we will pass along to those who might be interested in the resurrection of the works of the past, so that these works will not perish, so that the thoughts transmitted by them may endure, so that we may continue, as Dylan Thomas urged, to “rage, rage against the dying of the light.” This is not a bad legacy to leave for the ages, similar to the societal role we extend as professors: hand over the baton, and hope the newbies take possession of it in more or less the same condition in which you yourself had received it. We solve a problem, the transmission of the wealth of a republic, which is the very knowledge and information it needs to keep itself going, to persevere in its progression, to maintain its solvency, that is, for each generation to possess assets in excess of the liabilities of the preceding generation, in order to avoid dissolution and drip down the drain. We solve, and we are part of the solution, especially when in the classroom, and even frequently when out of it. Therefore I baptise us the Solutionists, and as I do so I am cognisant of the full panoply of cognates and connotations written now and in the past on the palimpsest we hold in our hand. I like to keep mine as shiny as a mirror, to reflect the past onto the present, to echo the pondering, the philosophical meanderings, the assessments of those long dead, for they might still hold sway on the honorable truths of our time. We are the universal solvent, limpid and transparent, striving to carry precious solutes to where they’re needed next. By these definitions, Voltaire was a solvent extraordinaire, as successful as water, for he carried forth so many solutes from the past, which he concentrated, distilled and deposited into his corpus, which, with the inexorable passage of time, may, or may not, reach our solution hole today, or, if anything, reach it whole.

Death came to Voltaire when he was 84 years old. A couple of months before, he had seen his latest play, Irène, greeted on the stage to thunderous applause. Marie Antoinette herself had come to its opening night, and she memorized some of its lines. But his last play, Agathocle, was already a finished manuscript; it would debut to great acclaim posthumously a year and a day after his death. The very devout Louis XVI, the one who’s to lose his head during the Revolution, had forbidden his subjects to talk or write about Voltaire or to produce his plays for a year. It could have been ten years, the public still would have clamored for the best seats in the house. In order to see Voltaire, the great Voltaire. The last Voltaire.

Today, Candide continues to enjoy a popularity that shows no sign of abating. Still, as the Solutionists, we must gently but urgently push you to read Voltaire’s book on India, either in French: Fragments sur quelques révolutions dans l’Inde, published in 1773; or in English: Fragments Relating to the Late Revolutions in India, published in 1774. I suggest you try a university library, one that keeps very old books. Books.google.com is another source worthy of exploration. Let’s all read it, before we go to Mars and trash the place, or something.

So, expect in the pages to follow glimpses of arcana dusted off and brought back to the light, treasures that have been long forgotten, because those who held the power were the ones who wrote the history, shrouding what they deemed dangerous, hiding knowledge that they wanted expunged from the world, or demonizing it into oblivion. The truth as it was, non-filtered and unmediated, is what we Solutionists want to retrieve from the past. As daunting as that may seem, we garner courage from the artists and thinkers of the past, and they shall speak through us again.

We also invite our readers to uncover from their own personal solution holes their favorite lost treasures of the past, to bring up from the depths of limbo the legacies of forebears who are in danger of falling into oblivion. Send us your resuscitations that we may publish them in the SolutionHolePress.com blog, and keep the lights twinkling

0 Comments