The Discounting of Books

Braund’s Bookstore (not its real name) is chockablock with books. We’re groaning under the sheer weight of the stacks. We have been obliged to build towers of tomes over the books on the highest shelves, where there are no more shelves. We have been forced to keep stacks on chairs, on the hand truck, in the aisles off to the sides, on our foyer table, which we vowed would be forever free. Duplicates are placed behind the rows, and in a special bookcase in the back storeroom. I’ve been eyeing specially-made-for-tight-squeezes elaborately outlandish bookshelves touted on the Internet, some of which hang from the ceiling like swings. Only tall people would have to duck, me especially.

Braund’s Bookstore (not its real name) is chockablock with books. We’re groaning under the sheer weight of the stacks. We have been obliged to build towers of tomes over the books on the highest shelves, where there are no more shelves. We have been forced to keep stacks on chairs, on the hand truck, in the aisles off to the sides, on our foyer table, which we vowed would be forever free. Duplicates are placed behind the rows, and in a special bookcase in the back storeroom. I’ve been eyeing specially-made-for-tight-squeezes elaborately outlandish bookshelves touted on the Internet, some of which hang from the ceiling like swings. Only tall people would have to duck, me especially.

We are busting at the seams, and still they come, in car trunks and in cartons, in grocery bags, suitcases, wooden crates and plastic milk boxes, and in people’s arms. Just yesterday, a tall sturdy young man brought in four huge heavy-duty plastic bags of books, as if they were garden clippings, including a beautiful boxed set of Plutarch’s Lives. Oh, the indignities books must undergo! But still they come, a barrage of tomes falling tumultously on us. It’s been a deluge, a tsunami of books, careening across town and down into the funnel of Braund’s, where we toil daily to subdue the tidal waves. Cassandra (not her real name) calmly explains that the economy is still not upright because too many people are divesting themselves of their books, or else they are rummaging around Florida rooms (we don’t have attics) or in the storage rooms belonging to relatives hoping to make ends meet by selling off their great-aunt’s Spanish classics or the children’s books that their progeny read when young. This summer, especially, we had incoming just about every day, sometimes several times a day. We have some sellers who break my heart, like Elena (her real name), who has mostly sold us her daughter’s and niece’s books, plus any others that she is able to cull from her neighborhood. She tells us stories of how Social Security is not enough, and why she never got a pension from the company she worked for. Cassandra always gives her more money than her books are worth.

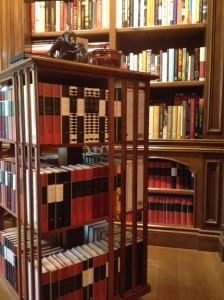

True, there are many other kinds of sellers who are compelled to sell parts of their libraries for reasons that have nothing to do with the stagnant economy. Those, for instance, who are forced to move. (Although they are probably forced to move because they are chasing jobs across the state, across the country.) When a whole library is to change hands, the client calls us, and Cassandra sends me, Lou Ryan (not my real name) to visit the premises and investigate the books. I find myself the Johnny Depp of book merchants from the Roman Polanski movie The Ninth Gate, and my ego inflates so that my lungs can barely breathe. Reality, however, has this usual habit of letting the air out of my balloon. Not the elegant, exquisitely polished mahogany libraries depicted in the movie, no, far from it. Alas, I am no Johnny Depp, either. I find myself in a hot musty bungalow, or a low-ceilinged townhouse or dusty apartment in full disarray, furniture topsy-turvy that is in the process of being moved across the room, across the house, with accompanying yard sale for neighborhood scroungers. All is bedlam, except for the books, that is. They are usually still ensconced in their original bookcases, at worst with some volumes missing, those that will follow their owners to their new digs. All book owners who move do insisit on moving with some of their favorite books. This is what I have done all my life, although I hope to be in my last house, because my partner and I built it to our specifications, and mine included a dedicated Library, good for 5,000 books, on the second floor overlooking the garden. My other 5,000 books are in other rooms of the house, especially the Reading Room, next to the Library, and the Guest Bedroom, also on the second floor. The Kitchen has about fifty cookbooks, with an overflow into the Media Room of another twenty, plus about a hundred oversized Decorating, Art and Travel books. Oh, and the Music Room has antique books that were placed there by one of our interior designers, more for their looks rather than their contents. They are, however, hugely readable, and one set, an 1811 12-volume collection on Medicine, I actually consulted for my novel Lord of Reason, to gauge how much was known about Voltaire’s illness, cancer of the prostate, which was what finally caused his demise at the age of 84 years.

To bibliophiles, detaching themselves from some of their books is painful at best, a trauma at worst. This is the wicked and dismal way of the world, and Braund’s finds great books this way. Since I myself, obdurate bibliophile that I am, know how it would feel to let books go, I try my darnedest to assuage the sorrow for others, to soften the blow, to mitigate the anguish that they feel. A retired osteologist was being made to move by his children from our coast of Florida to theirs, and he sold us a third of his quite extensive library. Our science, philosophy and literature sections gained tremendously. I spoke to him at length, however, about retaining only his best books, about his remaining collection improving in quality, and I meant it when I said that at his age he didn’t need all those books on philosophy, since he could now write, with confidence and authority, some of his own. The literature books, too. I told him that he had read them, assimilated them, and that they were now part of him. Was he going to have time to reread them at any point in the future? This last statement is one that I also direct to myself, and I try to believe it for myself. I read War and Peace twice before I was twenty, but not since then. I keep promising myself to reread it, now that I am nearing sixty, not just to revisit a great old friend, but also to see how much I have changed, such change to be measured by my new reactions to this old friend. I am particularly interested in my new response to Pierre Bezukhov’s religious doubts and existential turmoil. That angst fit me fine when I was nineteen, and I was having my own spiritual confusion, but now that I’m a cantakerous old atheist, will Tolstoy succeed in maintaining my patience and tolerance for his character’s anxiety? I anticipate the pleasure: it will be grand to be back in the world of Tolstoy, Napoleon be damned.

In another lamentable scene of book-letting (similar to blood-letting), a middle-aged, but still quite beautiful, screenwriter was moving permanently to California, and she was selling part of her own library, and her mother’s and aunt’s libraries, in toto, as well. Her aunt had recently passed away, and her mom had a terminal illness and was in hospital. It is in the background of such tragedy and profound sorrow that books sometimes get turned loose to regain their peregrinations. But this daughter and niece seemed to take the losses in stride: I admired her strength and sense of inner peace. Here was a reader who had taken to heart the books of philosophy and of life with which she was surrounded. She had the courage to part from fifteen boxes of books, and Braund’s Spanish-language collections were greatly enhanced, especially in Philosophy, Literature, Anthropology and Religion.

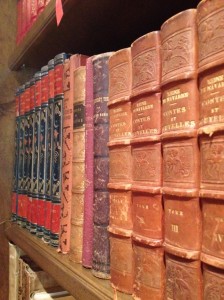

A bibliophile uncle of a normal (read: non-bibliophile) family passed away. Braund’s acquired huge sets of leather-bound books from The Easton and Franklin presses, gorgeous, in pristine shape. An artist on the beach sold us his collection of Art books. A university professor retired, giving up his library of arcane titles of Medieval and Renaissance literature and sociology, written in Italian and Latin. French, German, Swedish, and Dutch nationals come in and sell us their books. Of course, Latin Americans, from Mexico to Patagonia, are constantly coming in. Just yesterday, a Peruvian brought in manuscript books from the Sixteenth Century! (They were way too valuable for us.) We place our books according to subject, not language, so a book written in Spanish about Beethoven’s music will be placed under Music. One written in Greek of Cavafy’s poetry will be placed under Poetry. Only dictionaries of other languages and books on how to learn these languages are placed in Foreign Languages.

All our categories are in great shape, and we have no more space. The Occult is pressing on Cookbooks; Gardening is overtaking Anthropology, which not only is holding its own, but is fighting back. Plays have busted their barricades and are running in three directions: up above the highest shelf, to one side into Entertainment, and across the aisle to the bottommost shelf of Children’s. War, which already had three huge bookshelves dedicated to it, has shot up into a tower kept up with leaning buttresses of books, and has spilled down to run along on the floor at the base. It’s besieging Espionage and Crime, attacking the airspace above, and invading new unclaimed territory. The Revolutionary, the 1812, the Civil, the Crimean, the First World, the Second World, the Vietnam, and now Terrorism, damn, damn, damn, but there are way too many war books, for there are way too many wars!

Before we are swept away in a tidal wave of books, we need to send many off, at rockbottom prices, or even free. For years, Cassandra has arranged for Vietnam Veterans to come to the premises to remove the freebies. They are now coming on a weekly basis. This is not enough, anymore. We’ve had entrepreneurs purchase the cheaper books, $5 or less, at a steep discount, which they turn right around and resell at Flea Markets and Church Bazaars. Mind you, these are good, sturdy hardcover tomes whose only sin has been to have been produced in too large a number. (We don’t even carry mass-market paperbacks at Braund’s; there’s a bookstore across town that specializes in those.) But it’s still not enough to be giving books away for free. We need to start finding new places to donate books, perhaps at hospitals or social organizations.

Does this mean that the Era of the Book is coming to an end? Hardly. We have enough remaining books that not only warrant being kept in the stacks, but are justified in being placed on our online lists, where they can be snapped up by a book buyer anywhere in the world. We’ve sold to most countries in the world, although I don’t recall Cassandra ever selling a book to Russia. This in spite of the fact that we have a number of publications written in the Cyrillic alphabet.

Don’t let the cover of the book fool ya. We’ve found little books of 90 pages that turned out to be worth over $100. Super-grand coffetable books worth only $10. Cassandra has a guideline that’s proven useful: the more difficult the subject matter or the less she understands the title, the more valuable the book is apt to be. Longrun, it’s the market that prices books, with supply & demand, but rare books can only get rarer. Moreover, it’s a world market now, because bookselling organisms know no borders. Abebooks, Alibris, Biblio, Ilab, etc., function internationally, and some of these services allow you to bookmark a title you’ve been aching to have, so as soon as it comes online in San Francisco or Paris, in Buenos Aires or Geneva, you get an email to announce its appearance. Today, the whole world is your bookstore.

0 Comments